On June 17, 1933, Kansas City experienced one of its most tragic events to date at Union Station – the infamous Kansas City Massacre.

The public was left stunned and the entire nation was impacted by the event, which brought about a new era in law enforcement in America. Kansas City was no exception to the shock waves that were felt, as the incident had a profound effect on the city.

Frank “Jelly” Nash, a notorious American bank robber, had gained a reputation as one of the most successful criminals in history. In 1930, he managed to escape from the U.S. Penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas, where he was serving time for assaulting a mail custodian. Since then, he had been on the run, evading capture and continuing his life of crime.

In 1913, the criminal was sentenced to murder, and in 1920, he was convicted of burglary involving the use of explosives. Nash’s criminal record also showed that he had connections to organized crime, which could have contributed to his pardons for both offenses.

After Nash’s escape, the Federal Bureau of Investigations initiated a nationwide search, extending to some regions of Canada.

Frank Smith and F. Joseph Lackey, two FBI agents, along with McAlester, Oklahoma Police Chief Otto Reed, conducted an investigation that led them to Hot Springs, Arkansas. There, they successfully located and apprehended Nash.

After escorting Nash, the officers took him to a train station where they all boarded a Missouri Pacific train bound for Union Station in Kansas City. The plan was to travel by train to Kansas City and then drive Nash to the penitentiary in Leavenworth. As part of their plan, they also got in touch with Reed E. Vetterli, the special agent in charge of Kansas City’s office, who would join them at the station upon their arrival.

Nash’s arrest and whereabouts were a mystery to many, as it remains unclear how his associates found out. The prevailing theory suggests that John Lazia, a prominent figure in Kansas City’s criminal underworld who wielded significant influence over the police department, may have leaked information about Nash’s situation.

Some people are suspicious about federal agents speaking with an Associated Press reporter and informing them about Nash’s arrest and transfer to Leavenworth. They believe that Nash’s associates could have learned about it through the newspaper, which published an article about his arrest and transportation.

The FBI reports that the plan to free Nash was devised by Richard Tallman Galatas, Herbert Farmer, “Doc” Louis Stacci, and Frank B. Mulloy. They determined that Vernon Miller would be the most fitting candidate to execute the plan.

On the night of June 16, Miller had a meeting with gunmen Charles Arthur “Pretty Boy” Floyd and Adam Richetti where he shared his plans with them.

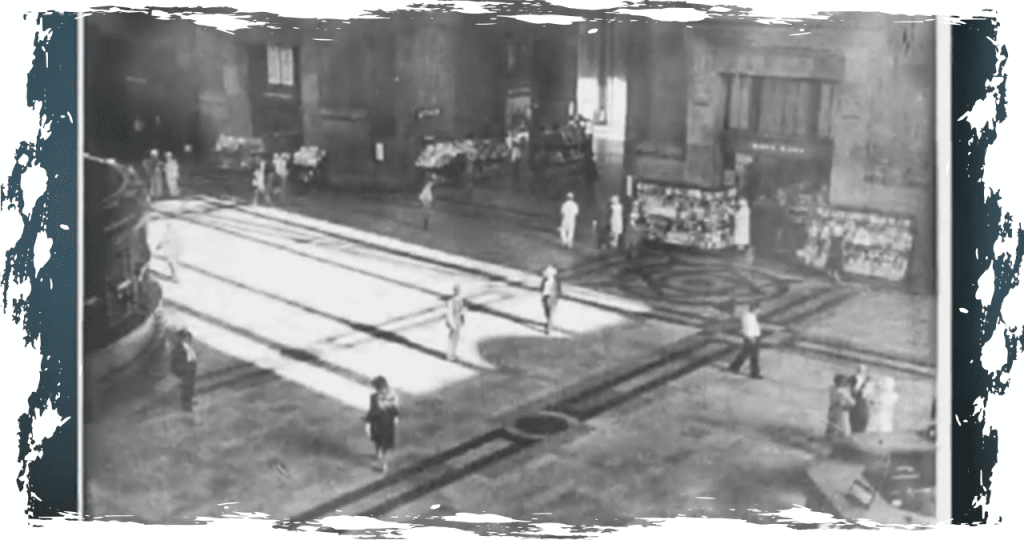

On the morning of June 17, Agent Lackey connected with Vetterli upon the train’s arrival at Union Station. Vetterli had FBI agent R.J. Caffrey and detectives W.J. Grooms and Frank Hermanson from the Kansas City Police Department with him to aid in the transfer of Nash.

Upon assessing the surroundings, the officers concluded that it was secure to transfer Nash from the train to one of the cars parked by Caffrey and Lackey just outside the station.

KCPD detectives Grooms and Hermanson, FBI Agent Caffrey, and Chief Reed lost their lives in the assault, while Agent Vetterli sustained a gunshot wound to the left arm. Additionally, Lackey was gravely injured after receiving three gunshot wounds.

The Kansas City Massacre is often cited as the pivotal moment that forever altered law enforcement practices in the United States. Within a year of the incident, the FBI was granted the power to carry firearms and make arrests by Congress.

According to research conducted by the KCPD, it was long believed that the marks on the front of Union Station were the result of bullet holes from the shootout. However, it has been established that the marks could not have been caused by gunshots. Nevertheless, the event remains a significant part of the rich history of Kansas City.